Dr. Ben Thomas, AIA Director of Programs, is an archaeologist who studies ancient Maya settlements and architecture as well as an Assistant Professor at the Berklee College of Music where he teaches Mesoamerican art and archaeology. Dr. Thomas shares with us why you should know archaeologist and artist Tatiana Avenirovna Proskouriakoff, a female Russian-American whose work contributed to the understanding of Mayan written language.

What got you intrigued about Tatiana Proskouriakoff?

Tatiana Proskouriakoff was a brilliant scholar, artist, and architect who challenged the idea that the inscriptions on ancient Maya monuments contained only calendrical and astronomical information. Through her groundbreaking work, she showed that the inscriptions were records of historical characters and events. Her work was the foundation on which Maya archaeologists built the political history of the ancient Maya.

Born in Russia, Proskouriakoff moved to the United States with her family in 1916. Ten years later she enrolled at the Pennsylvania State College School of Architecture—a woman in a program dominated by men. When she graduated in 1930, the US was at the beginning of the Great Depression and jobs were hard to find. After a stint at a department store in Philadelphia, Tania, as she was known to her friends and associates, took on a low-paying position at the University Museum of Pennsylvania where she used her considerable artistic skill to create drawings for one of the curators.

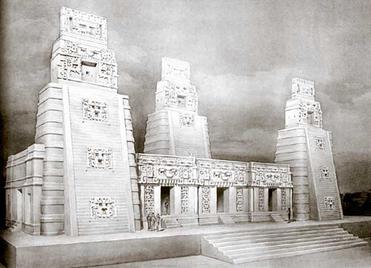

Tania’s artistic abilities were noticed by Linton Satterhwaite, the museum’s research director and the field director for its excavations at the Maya site of Piedras Negras in Guatemala. Satterhwaite invited Tania to join his 1936 expedition to Piedras Negras and gave her the assignment of making architectural drawings of the site. Once again, she was the only woman in a field project dominated by men. Tania’s stunning reconstructions of Piedras Negras were noticed by another pioneer of Maya archaeology, Sylvanus Morley of the Carnegie Institution in Washington DC. Morley sent Tania to the site of Copan in Honduras in 1939 and later to Chichen Itza in Mexico. By 1940, her talent and hard work had earned Tania a full-time staff position at the Carnegie Institution. She was there until 1958. In 1958 she moved to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University and remained there until her retirement in 1977.

Please share one anecdote that you see as representative of Proskouriakoff and her work.

Even today, archaeologists familiar with Tania’s architectural reconstructions, are particularly impressed by her ability to look at a ruined structure, visualize it as it once was, and illustrate it with artistic precision—her prescience often confirmed by later archaeological activity.

This is illustrated in an essay on Tania that was included in a series on the “Pioneers in Maya Archaeology” put together by the Institute of Maya Studies:, “during her first season at PN, her architectural training led her to believe that there should be a stairway on the side of one of the structures she was mapping. Satterthwaite had concluded otherwise, but provided her a crew to dig, as a way of proving she was wrong. To Satterthwaite’s bewilderment, the young architect was right. During this expedition, Proskouriakoff proved to be resourceful in adverse conditions, intuitive about the architecture of this Classic civilization as well as an excellent surveyor and artist.”

What do you see as Proskouriakoff chief achievements?

Included in Tania’s numerous achievements are two discoveries of considerable importance to Maya studies. Her main one, as mentioned above, was the recognition that inscriptions on Maya monuments were not exclusively calendrical and astronomical in nature but rather that they were historical records of events in the life of historical characters. Her conclusions were published in a 1960 paper entitled “Historical Implications of a Pattern of Dates at Piedras Negras, Guatemala.” According to Maya scholar, Ian Graham, “at one blow, this short paper freed the study of Maya writing from a lengthy stagnation” that “was truly liberating.”

Even before publishing the 1960 paper, Tania had begun to revolutionize Maya scholarship by establishing a method of dating Maya monuments that was based on morphology and sculptural style rather than on an examination of aesthetic values—the commonly used process at the time.

Through a systematic and rigorous analysis of around 400 monuments that included inscriptions with dates, she put together a process to date any monument without an inscribed date to within 20 or 30 years.

Tatiana Proskouriakoff never earned a degree in archaeology but her contributions to Maya archaeology, the understanding of Maya political history, and the decipherment of ancient Maya writing fundamentally changed our understanding of the ancient Maya. In 1998, fourteen years after her death, her ashes were interred at the site of Piedras Negras.

Finally, explain in 50 words (or so) why Tatiana Proskouriakoff is an archaeologist the public should know more about.

Tatiana Proskouriakoff was a true pioneer of Maya archaeology. A woman in a field dominated by men, she made her greatest contributions to the field by using her academic training and insight derived from systematic and rigorous work to challenge prevailing ideas. Her work made it possible for the many archaeologists who succeeded her to continue to expand our understanding of the lives and histories of the ancient Maya.

To learn more about Tatiana Proskouriakoff and her work, explore the following resources: