Affiliation:

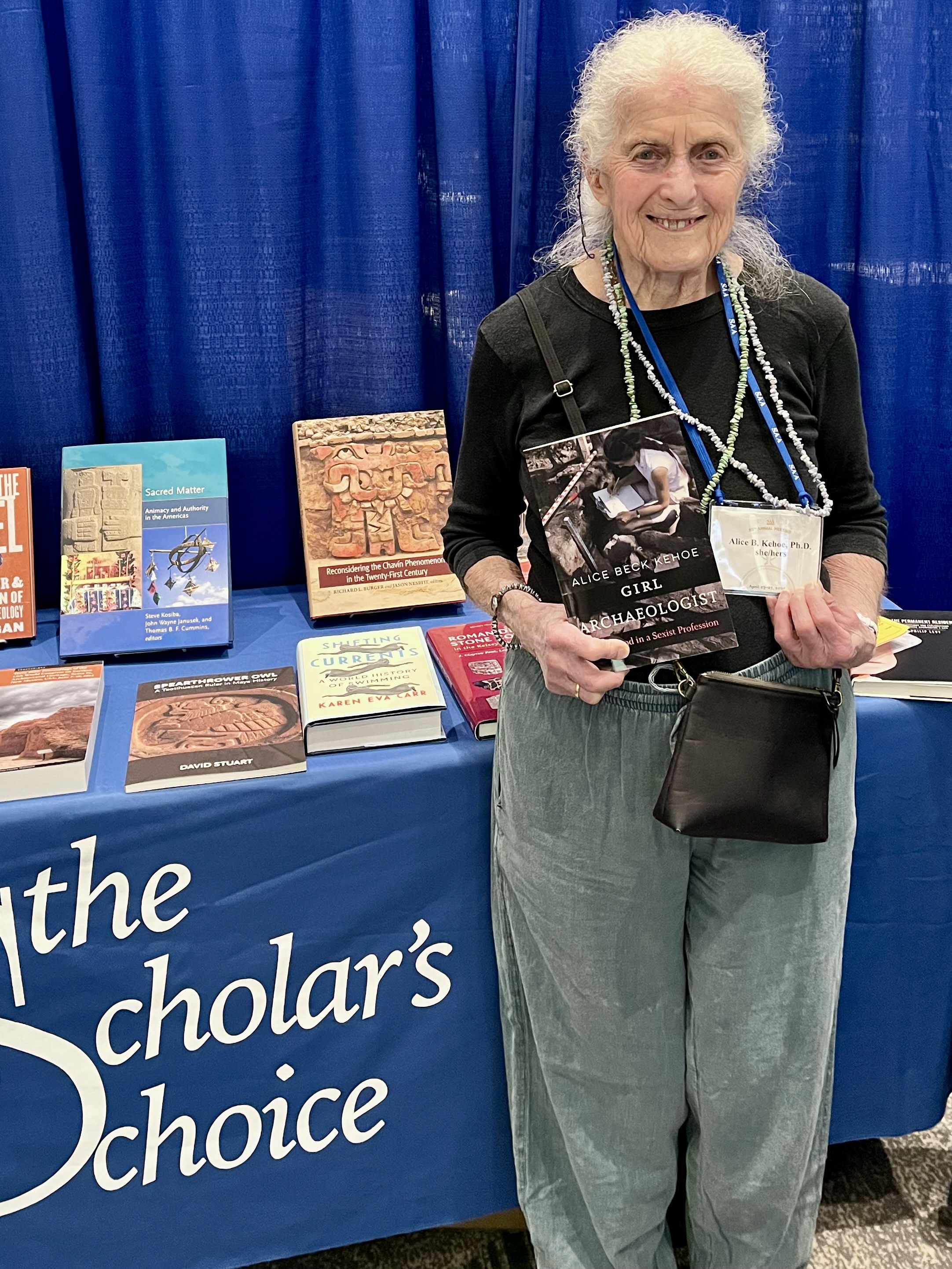

Alice Kehoe’s experiences in archaeology range widely from fieldwork on the Northwestern Plains of North America, to Upper Paleolithic sites in Europe and Tiwanaku in Bolivia. Her long-term interest in the history of archaeology includes research in Scotland on the introduction of the concept “Prehistory” (1851), on the 1493 Doctrine of Discovery that set up archaeological interpretations in colonies including America, and on how the historical sciences including archaeology differ radically from STEM sciences. At Society for American Archaeology’s 2025 conference, Kehoe was honored for her research and for her active leadership of women in archaeology.

Art historians have studied “the male gaze” of painters depicting nude women. Men’s fixation upon women’s sexual features extends into archaeology, where artifacts may be interpreted as fertility goddesses and depictions of male genitalia denied to be such. The Upper Paleolithic site of Dolni Vestonice in the Czech Republic has both a clearly female figurine and also clear carvings of male genitalia, but for generations, archaeologists have insisted that the male carvings are extremely formalized female breasts. The lecture includes Roman soldiers’ brass ornaments that are exactly like the Paleolithic male genitalia carvings, a note on the British Museum’s collection of phalli kept in a locked room, and lingams in South Asia.

Archaeology, along with geology and paleontology, is a historical science. These sciences are radically different from the physical sciences grouped as STEM. Particularities, not statistics, are basic to the historical sciences, and critical data come from observing present-day descendants of earlier forms. How an archaeologist works as a historical scientist is illustrated with Kehoe’s work on two remarkable sites, Cahokia and Moose Mountain.

U.S. Federal law Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 turned upside down, the usual practice of taking objects and human skeletons from First Nations into museums for the general public. Now, museums must return objects and especially human remains to the First Nations from whose lands they were taken. The same intent was passed by the United Nations in 2017 as UNDRIP, U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Where archaeology students up to 1990 were taught that Indians no longer retained traditional knowledge nor rituals, now students are taught to respect First Nations’ treasured knowledge and work humbly with their communities. It is a full revolution in values and practices. The lecture draws upon Kehoe’s experiences with Blackfoot, Cree, Dakota, and Osage, before and since the NAGPRA revolution

U.S. and Canadian museums avidly collected artifacts of all kinds from Latin America, from mid-19th century on. Expeditions were supported by museum patrons and universities; they hired local people as laborers while ignoring ongoing local cultural traditions. Academic practices labeled regions and “cultures” that continue to channel research, in spite of better information from ethnographies and ethnohistories, for example on “Maya”. Recognition of shared histories and cultural traits around the Gulf of Mexico and along the Northwest Corridor between Mexico and the U.S. Southwest remains impeded by academic border walls.